Brettanomyces, also known as Brett, is a yeast that imparts plastic or animal aromas, such as sticking plasters, smoke, leather, or sweaty horses, to wine. To put it differently, Brettanomyces could cause spoilage in wines via the production of volatile phenol compounds. At first glance, these characters may seem unpleasant. However, many wine enthusiasts enjoy them and do not consider low levels of Brett in wine a fault.

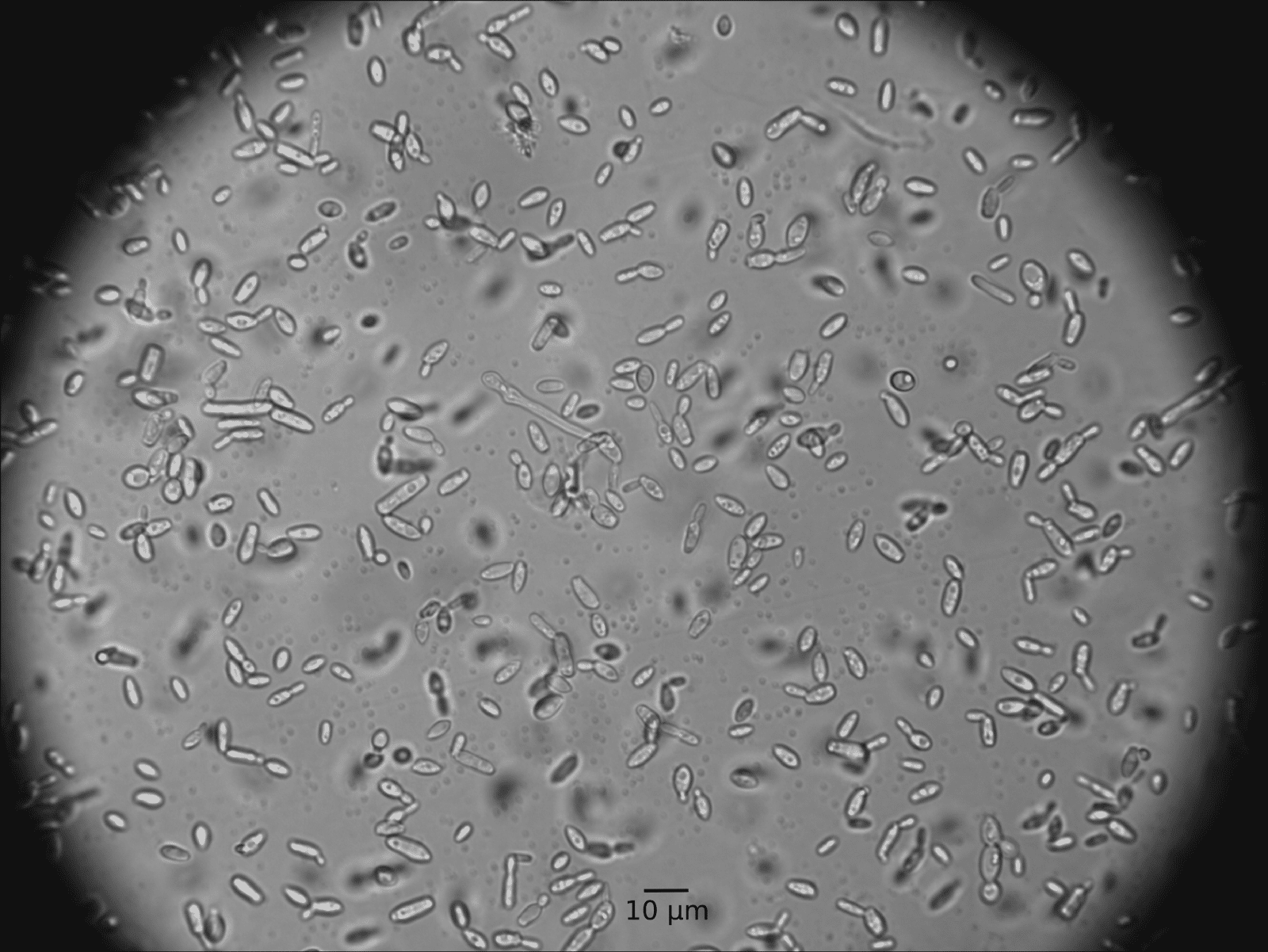

Brettanomyces belongs to a family of nine different naturally occurring yeast species (B. lambicus, D. bruxulensis, B. bruxellensis, B. intermidious, among others). Like its cousin, Saccharomyces, the principal agent of alcoholic fermentation, Brett feeds on sugars and converts them into alcohol, carbon dioxide, and diverse compounds that influence the wine aroma, taste, and texture. Unlike the compounds created by Saccharomyces, however, the ones produced by Brettanomyces are not so much appreciated. Some common descriptions could be barnyard, animal sweat, sewage, vomit, Band-Aid, and wet dog.

Different Growth

Apart from bestowing different aromas to the wine, the two yeasts differentiate in how they grow, too. For example, Saccharomyces multiplies in a must, feasting on all available fructose and glucose. It only dies when the food runs out, the alcohol content gets high, or the winemaker freezes the wine. On the other hand, Brett has steady but slow growth, and for this reason, it appears only months after the fermentation is over. Additionally, it feeds on a range of substrates. Fructose and glucose are favorites, sure, but Brett eats unfermentable sugars, as also oak sugars. Consequently, second-hand oak barrels can be a source of Brettanomyces infection.

As a yeast, Brettanomyces is a single-cell fungus. Fungi have two scientific names, one for the non-sexually reproducing form and one for the sexual, spore-forming version. When it comes to Brett, the spore-forming version is called Dekkera, but it rarely is seen in wine. Brettanomyces and Dekkera, however, encompass five known fungi species and an infinite strain number. Laboratories in Napa Valley, California, have isolated at least 70 of these.

Brettanomyces flourishes in any environment, and, therefore, it is not surprising that it thrives in cellars and vineyards. Regarding the nature of its aromatics, some wine fans consider the presence of Brett in wine as a flaw. Others, though, find that Brettanomyces contributes terroir elements. As expected, this debate seems impossible to be resolved anytime soon, as both sides have points.

Does Brettanomyces Affect Dry White Wine?

Most people believe that Brett does not infect white wine since they associate the barnyard and leather elements with red wine. However, Brett subsists on little food for a long time. As such, even a tiny amount of residual sugar (as low as 0.5 grams per liter) can support a large Brett population. To put that into perspective, viticulturists consider a wine technically dry when it has 2 grams per liter of residual sugar. Consequently, Brettanomyces any wine, including dry white wine, but not as much as red or sweet wines. In fact, there is an argument concerning the floral aromas of white wines. Some scientists believe that they can be associated with the presence of Brett.

Does Brettanomyces Favors High Alcohol?

The truth is that alcohol stresses Brett, just like every other yeast. That said, Brett can withstand a bit better than Saccharomyces, though.

Does Sulfur Dioxide Eradicate Brettanomyces?

Sulfur dioxide does not kill Brett but weakens it. Only pasteurization and Velcorin (organic compound) can kill the yeast and it can then be removed from wine through sterile filtration.

Does Brettanomyces Disappear Over Time?

While the aromas created by Brett might subside with time, yeast cells survive in wine bottles for an indefinite number of years in stasis. Under specific circumstances, they can return to life and become active again. Heat acts as an instigator and wakes up Brett, as well as sulfur dioxide when it breaks down over time. For this reason, Brettanomyces appears more frequently in warm areas or where there aren’t optimal storage conditions.

To conclude, Brett survives on malic acid, ethanol, amino acids, and residual sugars. Most of these conditions are generally ineffective to support typical wine yeasts. If Brett is not controlled it may gradually start colonizing even an entire winery and grow from imperceptible to dominant in flavor influence!

What Does Brettanomyces Taste Like?

Pinning Brett down to a black-and-white profile is challenging because it expresses itself differently in different wine types. Overall, it imparts spicy, savory, and stable smells to wines, as previously mentioned. For the most part, Brett smells of fabric plasters, but a phenolic and medicinal character is not uncommon. On top of that, on the palate, Brettanomyces gives a steely, metallic feel.

During its early stages, it takes away from a wine’s fruitiness. However, as it develops, Brett feeds on the unfermentable sugars, which give textual sweetness to wines. The result is a wine that tastes hard, without flesh. In most extreme cases, Brett is stinky with pronounced farmyard tastes.

Most winemakers know how to spot Brett early during the fermentation. From a winemaking perspective, Brett is hard to control. Taking advantage of its complexity during winemaking, therefore, is almost impossible. Winemakers cannot know if Brett will carry on developing once inside a bottled wine. As such, only a few, skilled Master Winemakers handle Brettanomyces deliberately. Undoubtedly, Brett is one of the most intriguing wine faults.

How to Avoid Brettanomyces?

The best practice to avoid Brett is to make an aging wine an inhospitable area for the yeast. This can be done in various ways. The presence of Brett can be controlled if there is enough sulfur dioxide in the wine. When sulfur dioxide is present, a significant portion of Brett is bound by it. The free Brett portion, though, is active. Still, if the pH is low, Brett cannot affect the wine. Therefore, wines with high pH are at risk of Brett. If the pH reaches 3.9 or 4, then sulfur dioxide cannot protect the wine against Brettanomyces.

The risk period for wines occurs between alcoholic fermentation and malolactic fermentation (MLF), when the sulfur dioxide levels cannot be high, as otherwise, MLF will not start. Because of this, winemakers opt for co-inoculation with chosen yeast and bacteria. Both fermentations take place at the same time, and sulfur dioxide is added immediately after.

Generally, winemakers seeking to avoid Brett add sulfur dioxide in a few large doses, as the sulfur knocks back Brett growth in an effective way. Besides, small sulfur dioxide doses do not really help. On the contrary, cold cellars do. In Burgundy, wines were fermented in barrels in deep, underground cellars. Just as alcoholic fermentation was over, the cellars would become cold, and the wine would remain there during winter at low temperatures. In spring, cellars would become warm, and malolactic fermentation would begin. Therefore, the Brett risk was gone since the wine was cold. In other words, the low temperature decreased the risk of Brett presence.

Increased Risk

Not every wine region is like Burgundy, however. Most wines are stored above ground in warehouses that are way warmer than cellars, which increases Brett risk. Even when winemakers stack barrels on top of each other, they face Brett problems, as, at the top of a barrel stack, the temperature is warmer than at the bottom.

Fermenting to dryness is another way to reduce Brett risk. As mentioned before, Brettanomyces loves feeding off residual sugar in the wine. And even if it is technically possible to find Brett in dry wine, the wines with lots of sugars are more at risk. Red wines with high phenolic content attract Brett the most, though.

Last but not least, Brett flourishes in wine bottles, too. For this reason, winemakers who feel threatened by Brett use sterile filters before bottling.