Phylloxera (Daktulosphaira vitifoliae) is an insect pest native to North America. Regrettably, the main Eurasian grapevine Vitis vinifera species is unable to defend itself against it. Consequently, it caused widespread destruction to the vineyards of Europe when it was accidentally introduced in the 19th Century.

Phylloxera has a complex life cycle, taking different forms throughout the year. During one phase, it lives underground and feeds on the roots of the vine. Infections enter through the feeding wounds, and over the years, the vine is weakened and ultimately dies. American vines, which evolved with it, can inhibit the underground insect by clogging its mouth with sticky sap. They also form protective layers behind the feeding wound preventing secondary infections. Phylloxera is a significant problem every year in most wine-making countries. However, there are exceptions, such as Chile, some parts of Argentina, and South Australia. Strict quarantine procedures are the only protection against this infection.

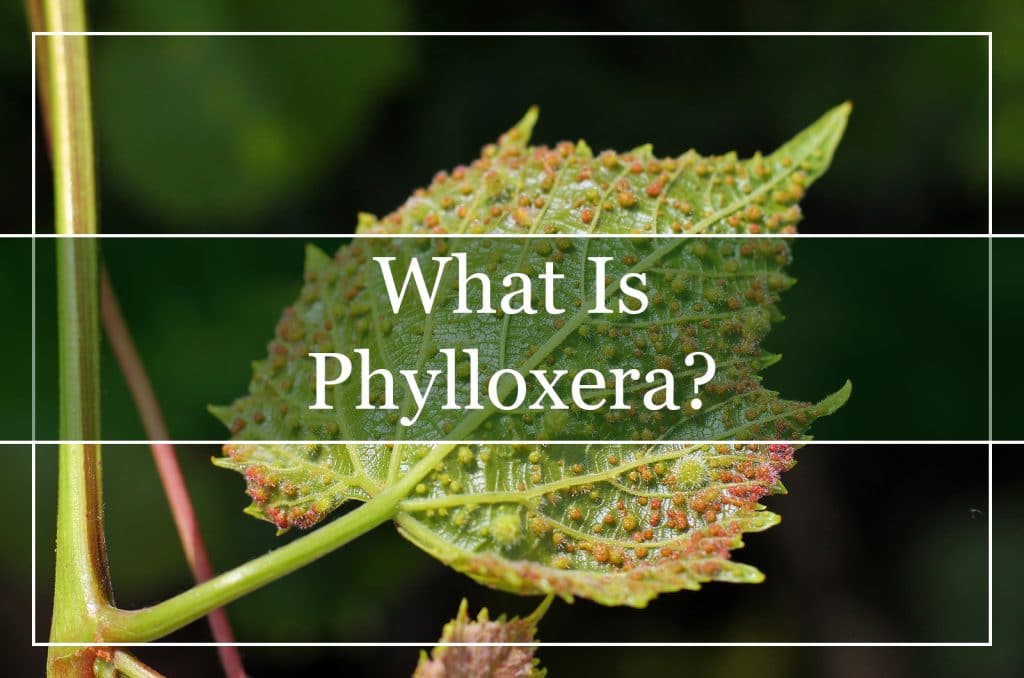

What Does Phylloxera Look Like?

Phylloxera (also known as grape phylloxera) is a tiny (less than 1 mm) insect pest that lives and feeds on vine roots. The insects are wingless and could be yellow-brown in color, pear or oval-shaped, or aphid-like. There are winged forms, too, but they are challenging to be seen and are also aphid-like. The only difference with the wingless forms is that they hold their wings flat over their backs. That said, neither wingless nor winged forms have cornicles, pipe-like structures on the abdomen, like aphids.

What Was the Effect of the Phylloxera Mite on the Wine World?

Phylloxera infestation threatened the world’s wine industry. It destroyed swaths of vineyards in many countries and winemaking regions. The pest was unstoppable, as its destruction spread beyond Europe, across New Zealand, South Africa, and California, too, among others. Only a few places were spared: Chile, Argentina, some areas in Australia, a couple of Mediterranean islands, including Santorini in Greece, and the Portuguese province of Colares.

When Did Phylloxera Hit Europe?

Phylloxera was introduced by accident to Europe from the United States. It created an epidemic that ravaged most European vineyards. In reality, it was introduced to Europe when botanists in Victorian England collected specimens of American vines in the mid-1800s. French vineyards took the gravest hit from this uncontrollable pest.

What Was the Great French Wine Blight?

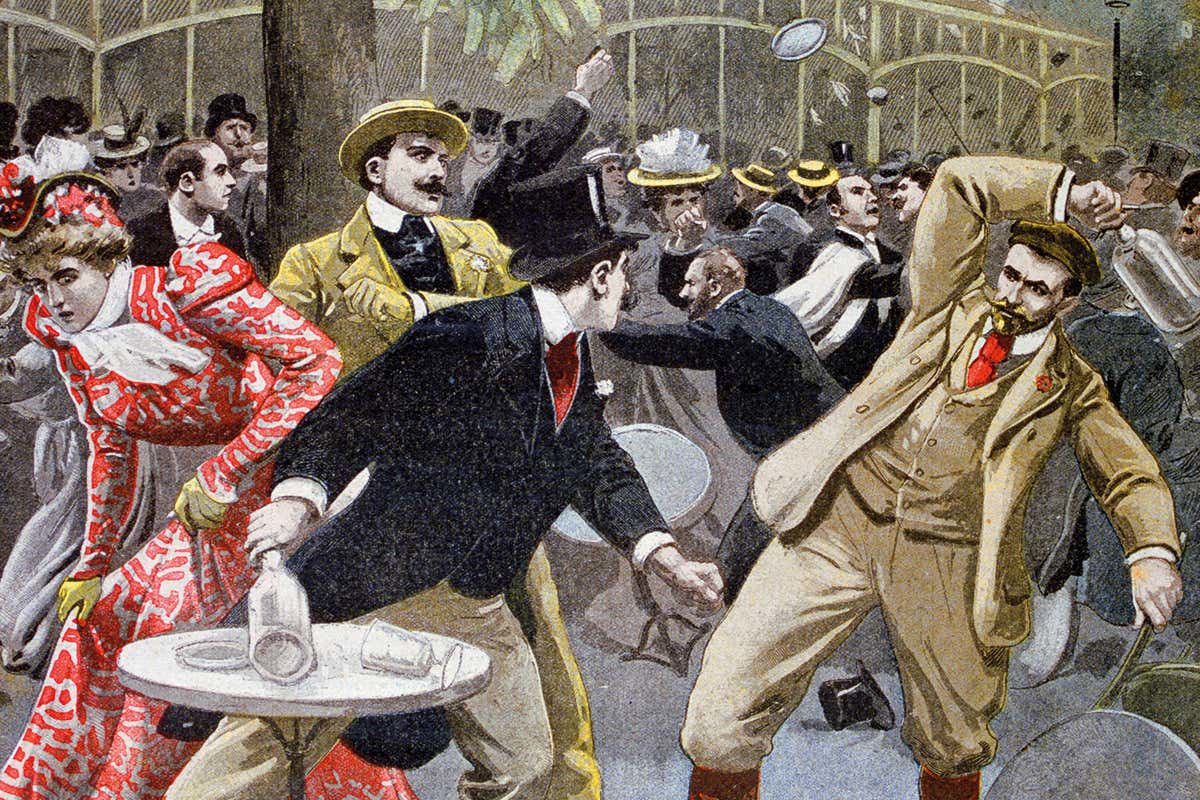

The Great French Wine Blight took place in the 1800s when the insect pest phylloxera infested and devastated French and European grapevines. The phylloxera epidemic was first noticed in 1863 in the Languedoc-Roussillon wine zone in South France and lasted until the 1870s.

Phylloxera seems to have been introduced to France by American wine vines that carried the pest. However, these vines were resistant to the aphid and not susceptible to it and its disease. During the blight, approximately 40% of French vines were ruined. In fact, wine production in France ceased. French winemakers were devastated and stricken by the lack of wine production. Phylloxera was resistant to chemicals and pesticides, so they could not do anything about it. That was until, they discovered that grafting French vines on phylloxera-resistant American rootstocks could stop the disease, saving the plantings.

Next, French winemakers removed countless phylloxera infected grapevines to plant new phylloxera-resistant ones. Unfortunately, this action led to the disappearance of most of the original French and European vines. Some vines, especially in France, Italy, and Spain, had been planted in Roman times, so they held historical importance. Nevertheless, the world’s wine industry survived, thanks to the resistant American rootstocks.

How Do You Identify Phylloxera?

The characteristic galls phylloxera produces on the roots or leaves, indicates the presence of the pest in a vineyard.

These leaf galls are wart-like and about 1/4 inch in diameter. And they are familiar, to be frank, to every grape grower. On the other hand, root galls are knot-like swellings on the rootlets and lead to the decay of infected parts. In fact, root galls caused the death of European varieties of grapevines, and due to them, almost all of the European wine production ceased in the 1800s, as mentioned above.

Additional signs of phylloxera infestation in a vineyard are leaf yellowing. On top of this, another major sign is the continuous development of weed growth under an infested vine. Keep in mind that these signs appear a long period of time after the infestation, typically after 1-3 years.

How Do I Get Rid of Phylloxera?

European grape varieties, as previously mentioned, have to be grafted onto American or hybrid phylloxera-resistant rootstocks. That said, the leaf form of the phylloxera causes damage to some grape varieties, independently of rootstocks. And foliar sprays to control the pest vary depending on the level of infestation.

But what most grape growers should do to protect their vines from phylloxera is to focus on prevention methods. Phylloxera spreads to new locations due to the unintentional movement of the insect by people. That means that it can be potentially transferred on grapes and vines through equipment that has been used in infested vineyards. It can even be transferred on the clothing or footwear of people moving from infested to non-infected plantings.

There is no effective long-term solution for controlling or preventing phylloxera. The use of tolerant, phylloxera-resistant rootstocks seems the only practical way to prevent damage and reduce phylloxera populations. Additionally, there are no known pesticides to provide effective phylloxera control.

Phylloxera is present on the leaves and the grapes of infected grapevines. Consequently, wine growers must treat the grapes or grape harvesting equipment in contact with the foliage or grapes contaminated with phylloxera accordingly.

Grafting with Phylloxera-resistant Rootstocks

Phylloxera cannot be controlled with chemicals. When it struck Europe, the only certain way to deal with it successfully was to plant American species or hybrids. By the end of the 19th Century, a better solution was found, though. Vitis vinifera could be grafted onto a rootstock of an American vine or hybrid. In this way, the American vine offered protection from phylloxera but helped the European vine keep its distinctive flavor.

Since this discovery, it has been found that rootstocks provide other advantages besides resistance to phylloxera, as well, and a large number of hybrids have been bred accordingly. For example, specific roots are used to protect against nematodes and provide better resistance to drought conditions. So, rootstocks are used in parts of the world where phylloxera is not a serious threat, despite the extra cost involved in purchasing grafted vines from nurseries.

What Is Grafting?

Bench Grafting

Grafting is the technique used to join a rootstock to a Vitis vinifera grape variety. The most popular method is bench grafting, an automatic process carried out by plant nurseries. Short sections of cane from both the Vitis vinifera variety and the rootstock variety are combined and joined by a machine and stored in a warm area to encourage the fusing of the two parts. Once this happens, the vine can be planted and cultivated.

Head Grafting

However, there is another way of grafting, known as head grafting. It is used if a grape grower with an already established vineyard decides to switch to a different grape variety between seasons. The existing vine is cut back to its trunk, and a bud of the new variety is grafted onto the said trunk. If the graft succeeds, the vine will develop fruit at the next vintage. A newly planted vine takes 3 years to produce a commercial crop. This technique, though, enables growers to adjust quickly to market changes. And it is also cheaper than replanting the whole vineyard, as the new variety begins life with an organized and reliable root system.

Which Country Has Never Been Affected by Phylloxera?

Even though the phylloxera pest devastated most of the European vineyards, some wine-growing regions remained entirely phylloxera-free. In Western and South Australia, for instance, phylloxera has never been found. Similarly, Riesling plantings in the Mosel region have also remained unaffected, since the parasite cannot survive in the slate soil.

Last but not least, Chile has remained free of the phylloxera pest. For this reason, Chilean grape vines do not need to be grafted with phylloxera-resistant rootstocks. Until today, phylloxera has never been found in Chile. Perhaps the fact that Chile is isolated from other parts of the world was beneficial in keeping the phylloxera epidemic at bay. Still, vines in Casablanca Valley might not be susceptible to phylloxera, but they are not free from pests and infections. They have trouble with nematodes or downy mildew disease.