Ampelography in botany is the field concerned with the classification and identification of grapevines. For the most part, ampelography has been done by comparing the color and the shape of the grapevine its leaves, and grapes. However, in recent years, DNA fingerprinting has revolutionized the study of vines.

A grapevine is not singular but a diverse species. For example, some grape varieties, like Pinot, mutate frequently. Meanwhile, the wine industries depend on the correct identification of different grape varieties and clones of grapevines.

As a science, ampelography gained prominence in the 19th Century. Back then, the introduction from the United States of phylloxera and other pests made the replanting of the European vineyards essential. In fact, it played a crucial role in identifying grape varieties and finding the correct rootstocks to counter these vine parasites. If ampelography had not been used, European vineyards would have been completely wiped out and not able to produce wine again.

What Does Ampelography Mean?

Ampelography derives from the Greek ampelos (vine) and graphe, meaning writing/description. As such, ampelography translates literally into the categorization and classification of grapevines.

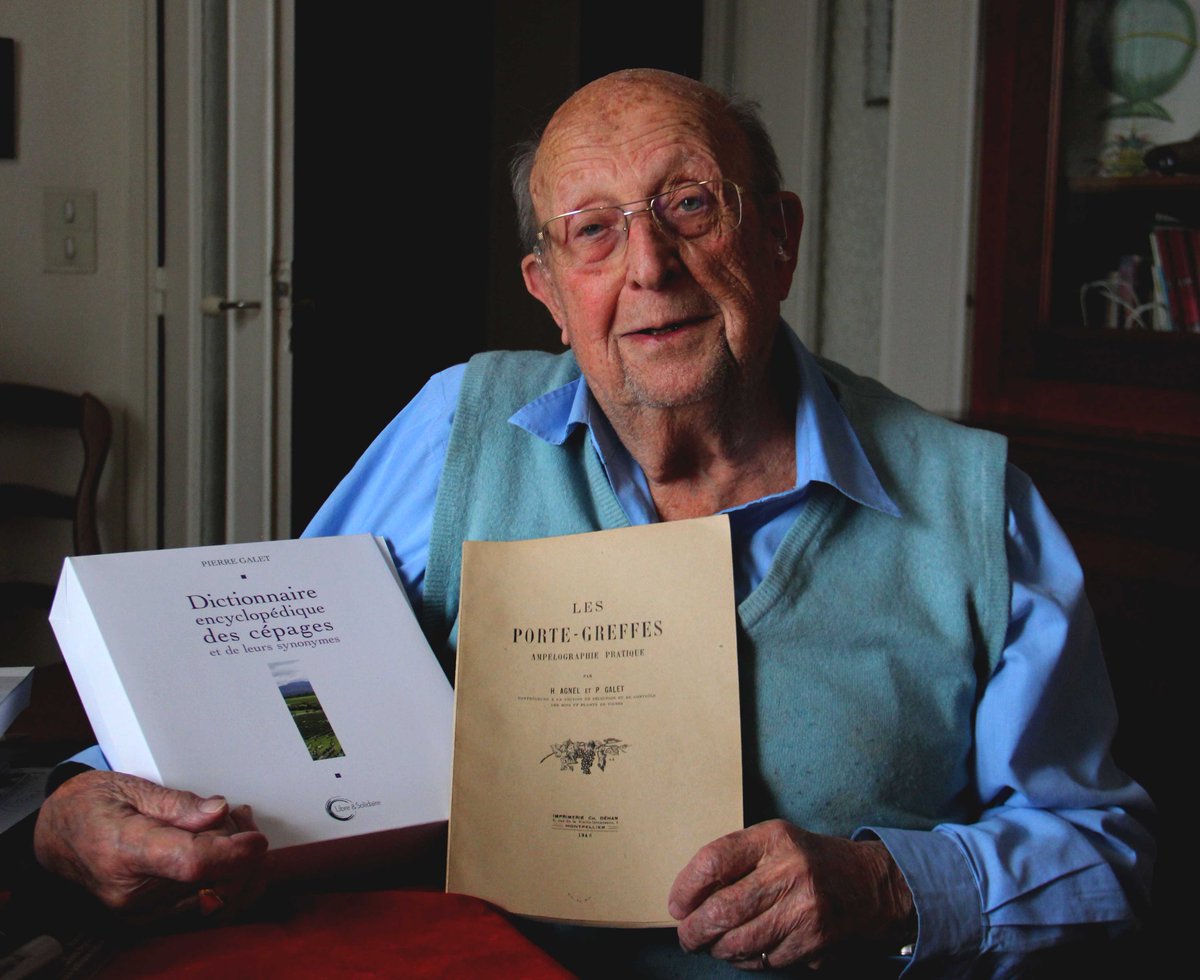

Pierre Galet: A Revolutionary Ampelographer

Up and until 1944, ampelography was considered an art. However, Pierre Galet, viticulture chair at the École Nationale Supérieure Agronomique de Montpellier, managed to identify and classify grapevines with the use of a systematic assembly of criteria.

This set of criteria now makes the Galet system, based on grapevine characteristics, such as shoot tips, growing shoots, the shape of the grape clusters, the sex of the flowers, and the color of the grapes. On top of this, the shapes of the grape leaves are vital in the identification of the vines, too. As they have a prominent position in the Galet system. He also indicated that environmental factors do not affect the grapes very much, unlike the shoots and the leaves, and he even considered grape flavor an important criteria.

Important Publication

When Galet became head of viticultural control at Montpellier, he started teaching grape growers and winemakers how to identify rootstocks. In 1952, Galet published Précis d’ampélographie pratique, a book that featured over 9,000 grape types. Précis d’ampélographie pratique was translated into many languages, including the English language by Lucie Morton in 1979.

Morton was not just a translator but a graduate student and protégé of Galet, too. He introduced her to ampelography, and during a car trip, Galet pointed out that the vineyards in southern France were from Vitis rupestris, an American rootstock. Vitis rupestris protected the French vines against the phylloxera threat. When she asked him how he could identify the rootstock while driving, Galet noted that he could do it by observing the leaves.

Identifying Grapevines Through DNA Research

Recently, DNA genetic fingerprinting, also known as DNA marker technology, has replaced traditional ampelography as a tool for identifying the origins of grapevines. DNA fingerprinting has been used successfully for vine identification on many occasions. The method involves establishing a specific DNA profile for each vine by taking samples from growing tips or young leaves. Then, viticultural scientists find a match in a relevant database. One such database is at the Foundation Plant Services department of the University of California, Davis.

DNA fingerprinting was pioneered by Calore Meredith at UC Davis. Dr. Meredith is an enology professor and the grapevine geneticist who solved the mystery surrounding the origin of Zinfandel, which gives the iconic rosé wine, White Zinfandel. Originally, Zinfandel was believed to be related to Primitivo. However, DNA research matched it to an identical Croatian variety, instead, Crljenak Kaštelanski. This technique also identified the parents of the Sangiovese grape as Calabrese Montenuovo and Cillegiolo.

Rich History of Grapes

Identifying grape varieties offers insights into migration and trade patterns. DNA-based identification is tremendously helpful because it is objective, unlike traditional ampelography, where the evaluation of characteristics is subjective. Furthermore, traditional ampelography has another weakness in comparison to DNA fingerprinting. Some components of grape varieties vary by region and, usually, do not look identical. So, identifying a grape family that spreads over different winemaking zones or even countries is challenging. On the other hand, DNA profiles are sets of numbers and are convenient to store and share among the viticultural community.

DNA fingerprinting uses DNA segments. These do not affect the grape taste or appearance. Recent genetic research identified the genes responsible for the differences between grape varieties, including the VvMYBA2 and VvMYBA1 genes that affect the grape color.

Despite the significance of DNA-based identification, there is a place for traditional ampelography as well. Expert ampelographers, for instance, can identify different varieties very quickly as they walk through a mixed vineyard. Consequently, traditional ampelography can offer quick and efficient answers, while DNA testing results take up to a week. With ampelography, ampelographers, just by looking at the leaves, can observe many things that DNA research cannot, like if a vine faced a frost recently.

What Does an Ampelographer Do?

The first thing ampelographers do when identifying a grapevine is to check the growing tip. That is if there is one, in the first place, of course. Then, they contemplate its condition. Some sample questions ampelographers ask themselves while assessing a vine: Does the growing tip have white cottony hair, is it shiny or hairless? Frankly, the hairiness is a solid identifier of the grapevine type.

Once this is over, ampelographers observe the leaf shape, if it has lobes or looks like a shield. Additionally, they consider leaf thinness or thickness or if the leaves are solid or have lots of indentations. For example, French hybrids have thinner leaves than most Vitis vinifera Eurasian grape species.

Next, they examine the petiolar sinus, which is the empty space that surrounds the leaf stem. Sinuses can be either open or completely unnoticeable. By comparing the petiolar sinuses, ampelographers can distinguish different grape varieties, such as Cabernet Franc and Cabernet Sauvignon from Merlot.

Moreover, the lobes and teeth distinguish grape leaves, too. As expected, some leaves have identifiable lobes, while others have none at all. As to the teeth, these are serrations on the outside leaf edge. Some teeth are sharp, while others appear more refined and rounded.

Vital Information

When combined, these segments help ampelographers discover the identity of a vine. Take, for example, the Cabernet Sauvignon vine. It is known for having downy mildew growing tip and rose-colored leaf edge. And the leaf sinuses have an overlapping edge that appears of being cut out with a hole puncher. On the contrary, Chardonnay has shield-shaped leaves with an open petiolar sinus surrounded by naked veins and sawblade-like teeth. Plus, Chardonnay’s young leaves have distinctive red clots, while Cabernet Sauvignon’s show a pinkish edge.

Ampelography offers vital information about grape clones, as well. Some varieties, such as Cabernet Franc and Pinot Noir, have easily identifiable clonal variations because they have morphological differences, meaning different leaf shapes and cluster features.