As a wine enthusiast, how would you evaluate the quality of wine? Swirl, sniff, sip, and swallow — these are the steps wine drinkers typically follow to understand the taste and texture of the wine.

However, during a wine tasting session, you may ask questions such as “How do I know a wine has the right aroma?” or “What gives the wine its earthy flavor?” Here is where wine sensory comes into play. Wine sensory refers to the formal evaluation of the aroma, characteristics, and flavors of a wine. A sensory evaluation provides a better understanding of a wine’s taste and texture, helping wine lovers analyze what makes a wine different or unique from other wines.

Let’s take a closer look at what wine sensory is, followed by a guide to wine sensory and techniques to becoming a wine sensor.

What Is a Sensory Guide?

A scientific discipline, sensory evaluation is used to induce, measure, assess, and interpret reactions to certain characteristics of foods and materials as perceived by the senses of taste, smell, sight, hearing, and touch. Unlike other food industries where consumers and producers enforce variations among food samples, winemakers expect several differences to emerge from multiple sources of wine, including blends, varietals, vintages, and regions.

Sensory evaluation provides various tools for examining these differences by analyzing and interpreting the reactions as perceived through sight, smell, hearing, taste, and touch.

When it comes to wine sensory, the sensory evaluation aims to address two questions — “Are the wines perceptibly different?” and “If yes, on what attributes are they different?” Methods of sensory evaluation follow strict protocols that have been approved by the ISO to reduce any biases that may influence one’s perceptions about wines, or any other product.

Difference Between Sensory Evaluation and Wine Appreciation

Wine appreciation involves a hedonic and technical evaluation of wines through practices borrowed from sensory methodology. A step-by-step process is followed to assess the wine’s appearance, aroma, body, taste, and persistence in the mouth. Little to no attention is paid to the psychological or any other bias that may occur while wine tasting.

Wine appreciation expects people to examine the quality of a wine, evaluating their perceptions and comparing them against the wine’s sources. For example what grapes were used, where they were cultivated, the winemaking process, and so on. Hence, the assessment of the wine is highly interlinked with one’s likes and dislikes.

On the other hand, a sensory evaluation does not provide any such information with regard to the wine you will be tasting. A sensory assessment might give you only minimal information, thus reducing the probability of personal bias as much as possible.

A Guide to Wine Sensory

To ensure that the sensory evaluation of wines is carried out impartially, it is important to do it in the most unbiased manner possible. For this, each glass of wine is presented as “blind.” No information regarding the grape varietal, vintage, type of producer, or source of grape is revealed.

Other than not disclosing any details about the source of wine, each wine is poured into identical glasses, in equal amounts, to create an identical headspace. The wine order is varied before presenting it to the evaluators, to ensure that the same wine is not tasted more than once.

Standardization is followed during the process of wine sensory evaluation to eliminate the possibility of any errors that may result from the process. One of the most stringent applications of the sensory evaluation takes place in research laboratories. Here further questions on consumer preferences, the key characteristics of a wine, and the factors that influence the cultivation of wine grapes are probed. Some of the most common sensory evaluation tests for wines include hedonic testing, difference testing, preference testing, and descriptive analysis.

Let us understand each of these tests in detail.

Hedonic Testing

Under hedonic testing, consumer-liking or preferences for a product is tested. Hedonic testing can also be used to understand the likes, dislikes, and choices that consumers make based on demographic factors such as age, income, location, and education.

Difference Testing

Difference testing aims to examine and determine whether two wines are significantly different from each other. This process is used to evaluate the effects of grape cultivation, treatments involved in winemaking, the number of vintage years, and aging trials.

Preference Testing

Preference testing is similar to hedonic testing as it tries to understand consumer preferences. However, the main objective of preference testing is to determine whether people prefer one type of wine over the other. It is usually conducted after the difference testing has been performed.

Descriptive Analysis

Under descriptive analysis, wine aromas and flavors are characterized in distinct categories. In this type of testing, judges or panelists, as they are called, first create a list of sensory descriptors such as cherry, chocolate, earthy, cinnamon, or leather. The list is made to describe the set of wine samples presented.

Later, each wine sample is examined and rated in terms of quality and quantity. While the quality aspect focuses on the descriptive indicators, the quantitative aspect emphasizes the intensity of each descriptive parameter.

Descriptive analysis is an important part of sensory testing as it is not only useful in understanding what makes a particular wine unique but can also help to assess factors such as the process of winemaking, grape cultivation, wine types, and regions.

One of the best and most preferred tools that people use during wine tasting sessions is the wine sensory or wine aroma wheel. The wine sensory wheel breaks down the different flavor profiles and aromas into multiple categories, allowing one to better identify what they are tasting or the smells that they are getting from the wine. Hence, the wine sensory wheel is one of the easiest guides you can use during a wine tasting or for wine sensory evaluation.

Techniques to Becoming an Expert Wine Sensor

So you want to become an expert wine sensor? Interested in performing a thorough analysis of wines free from any bias? Here are the techniques you need to follow to become a professional wine sensor.

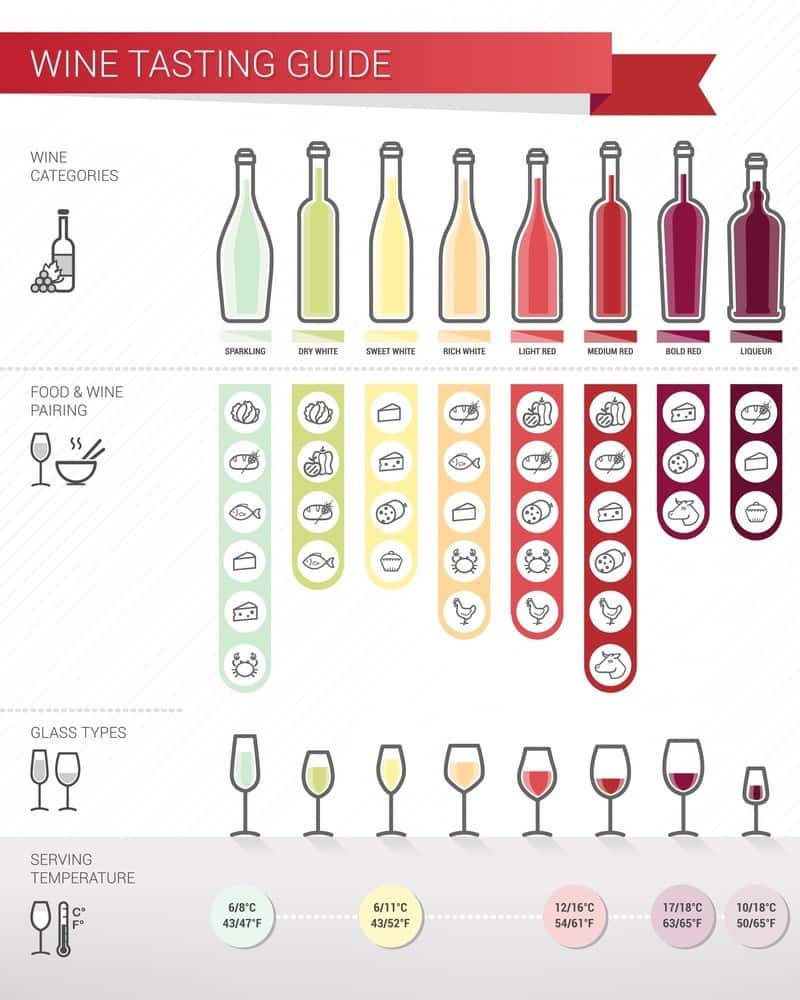

Typically, there are five fundamental steps involved in the process of wine sensory: see, swirl, smell, sip or swish, and savor. We will take a look at each of these steps in detail.

See

Seeing is the first step in wine sensory. Pour a glass of wine, hold it up to the light, and observe its color and clarity.

Swirl

The next step in wine sensory is swirling your glass. You need to hold your glass of wine either in front of you or on a flat surface. Then, slowly rotate the glass to get the wine moving. This will help you notice the “legs” of the wine or the droplets that form on the inside of a wine glass as you twirl it. This will help you figure out the alcohol levels of your wine.

They are also called the “tears of a wine” by the French, although these droplets or wine streaks cannot accurately tell anyone what percentage of alcohol is in your wine.

Smell

Besides being an indicator of the alcohol levels in a wine, swirling also helps to release its aromas because of aeration.

After you have swirled your glass of wine, take a deep breath to smell your wine. If you haven’t understood the aromas in the first go, you can take more than one sniff. However, you may have to swirl your glass more than once. You can also use the wine sensory wheel to pinpoint the aromas your wine closely resembles.

Sip/Swish

After you have figured out what your wine smells like, it is time to taste it. By tasting, we don’t mean gulping down the whole glass. Only take a few small sips.

Once you take a sip of your wine, move it all around your mouth, like mouthwash. You can either choose to swallow it or spit it in a dump bucket. Then, take another sip and repeat the same process. This time, however, you not only move the wine across your mouth but all over the tongue as well. This will help all your taste buds to come in contact with the wine and help you understand its taste better.

Keep the wine in your mouth for 3-5 seconds before swallowing it or spitting it out. This will allow the wine to warm up slightly and release its aromas.

You can also use the wine sensory wheel to categorize your wine’s taste accordingly.

Savor

The final step in wine sensory is savoring your wine. Arguably the best part of the process, you can now enjoy the rest of your glass of wine if you liked its taste and aroma. But don’t forget to observe its lingering effects in your mouth as it will help you evaluate the length of your wine. If the taste of the wine lingers in your mouth for 1 to 3 minutes, or even longer, it is a sign that your wine is of high quality.

Techniques to Better Assess Wine

While we have discussed the five steps in wine sensory and the use of a wine sensory wheel, here are some more techniques to keep in mind that can help you evaluate your wine even better.

Wine Appearance

The first and foremost step in wine sensory is observing your glass of wine to see its color, clarity, transparency, and other qualities.

When we talk about clarity, your wine can be either of the following:

Bright

Limpid, or completely transparent

Cloudy

Veiled

Opaque

A wine is considered to be of good quality if it is limpid and bright and does not have too much effervescence. Effervescence indicates the presence of bubbles and fizz, something that is characteristic of sparkling wines and champagne. If the glass of wine you are holding is not a sparkling drink, then it should not have too much fizz. Moreover, the finer the bubbles, the better the quality of the wine.

After this step, you need to check for your wine’s fluidity. Fluidity is assessed by the viscosity of wine when swirled. If the wine has a high viscosity, it will appear to have a thick and syrup-like texture, and if it has low viscosity, it will look watery.

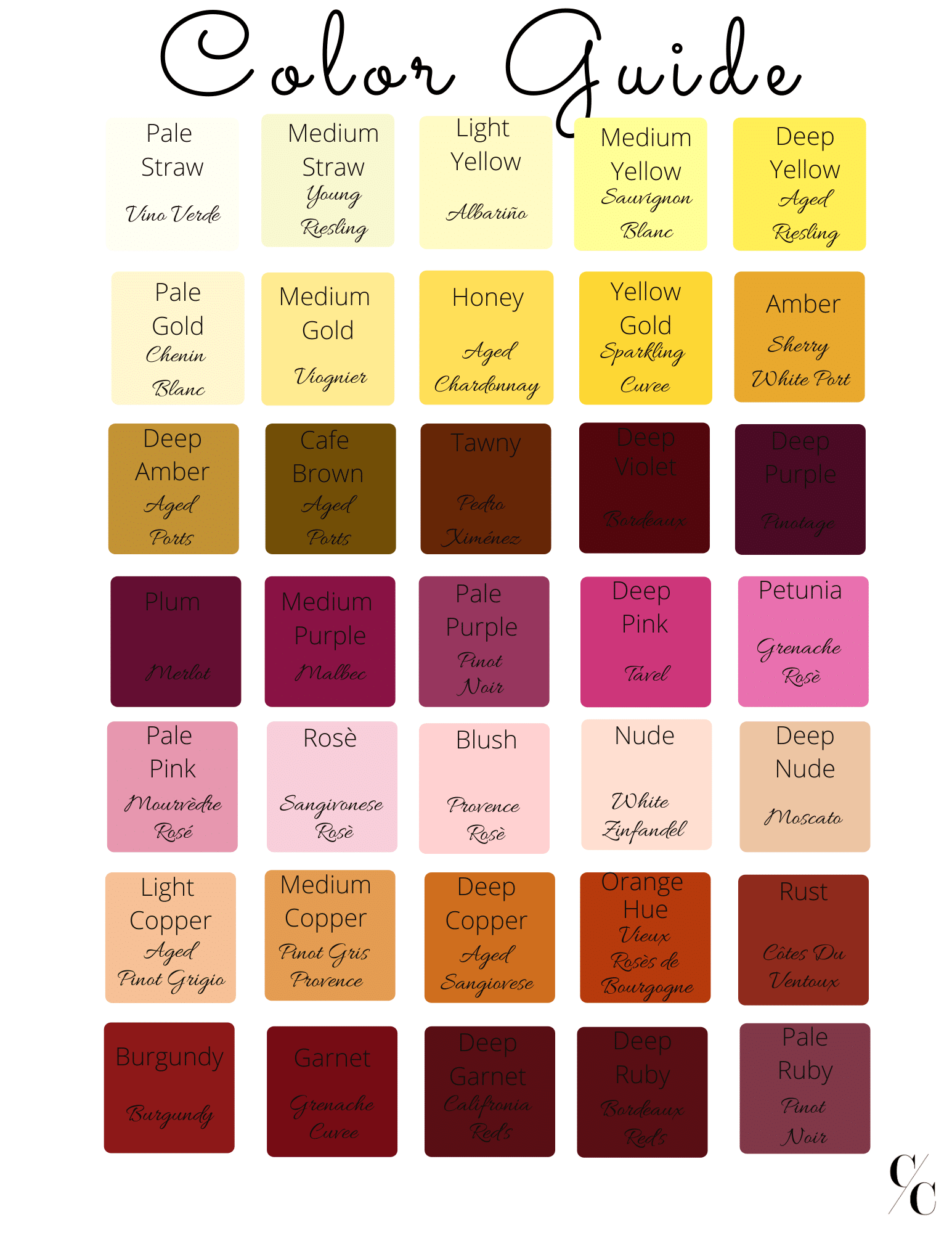

Color

Examining the color of your wine is a part of the observation process and can be classified according to its various nuances:

Red wines — Cherry, ruby red, orange-red, amber-red, pomegranate, crimson, brick, violet

Rose wines — Raspberry, onion skin, salmon, peach flower, powder

White wines — straw, golden, amber yellow, paper-white, green-hued, hay

Aroma

Evaluating a wine’s aroma is one of the most crucial parts of wine sensory as it is one of the easiest ways to understand the quality and finesse of a wine. It also gives you an idea of your wine’s elegance, intensity, complexity, and body just from its aromas. The depth and quality of the aromas emerging from your wine depend upon its production, evolution, age, grape cultivation, winery region, and the techniques used to grow the grapes.

Wine aromas have been categorized into various classes including:

Primary or varietal aromas, which resemble certain wine grapes

Secondary aromas, also called vinous aromas, that develop during the fermentation process

Tertiary or post-fermentation aromas that develop as the wine matures and rests in the barrels or bottles after it has been sold

One can classify wine aromas in various families as well:

Animal — hair, fur, leather, hide

Balsamic — pine, juniper, menthol, resins, balsamic oils, camphor oil

Chemicals — acetone, flint, sulfur, hydrocarbons

Phenolic or Burnt Smell — toast, smoked meat, incense, cocoa, coffee, caramel, cooked food

Etheric — esters of fatty acids, soap, nail polish, wax, flour, bread crust, yeast, butter, honey, freshly processed cheese

Floral and fruit-like aromas

Spicy — aromatic herbs, cinnamon, pepper, vanilla, fennel, licorice, nutmeg

Herbaceous — vegetable-like substances, tomato leaves, tobacco, sage, wet leaves, hay, underbrush

Taste

Tasting is the ultimate step in wine sensory and assessment. It is the step that judges the consistency of your wine and determines whether it is good or bad.

Tasting is also the easiest step in wine sensory since we only have four basic taste buds, sweet, salty, bitter, and acidic. While the principal sensations of the wine are perceived on the tongue, other characteristics of the wine are examined on the palate. Moreover, tasting can also involve observing how long the taste of the wine lingers in your mouth.

Here are some of the most common tasting parameters in wine sensory:

- Sweetness

To check the sugar levels of the wine. It can also help to tell whether your wine is dry, semi-sweet, tart, sweet, or friendly. If there is any sugar left after you have consumed a glass of wine, it is considered sweet; otherwise, your wine is dry.

- Alcohol Content

This helps to understand whether the level of alcohol in the wine is light, hot, vigorous, generous, powerful, or very high.

- Texture

Texture refers to whether your wine is thick, oily, soft, velvety, or coarse.

- Acidity

The acid levels in your wine can be understood if there is a lingering sour taste on the sides of your tongue, at the back of your mouth, or on your inner cheeks. Acidity can be classified as raw, green, sharp, savory, fresh, or flat. Typically, white wines have a higher acidity as compared to red wines.

- Tannin

Tannins are a sensation that develops on your tongue and leaves a dry taste later. They are usually associated with red wines and can be classified as austere, astringent, puckering, or rough.

- Structure

The wine structure can be defined as being light, robust, thin, pulpy, or full.

- Persistence

Persistence refers to how long the taste of the wine lingers in your mouth after you have swallowed it. The persistence or length of the wine can be described as short, medium, long, or extremely long.

- Development

Development indicates the age or maturity of the wine. Based on its taste, you can describe the wine as young, mature, ready, past, tired, or lifeless. It is said that the older the wine, the better its taste.

Conclusion

Wine sensory is a scientific process that takes time to master. If you are a beginner or are interested in learning about the techniques of wine sensory, it is recommended that you start with its fundamentals including how the wine preceptors can be evoked using our five senses and what possible biases can affect them. And if you are an experienced taster, you can always revisit your practices and look for ways to enhance your techniques.

You should also be aware that wine sensory is different from wine appreciation. However, there may be times when wine sensory may be clouded by biases. Thus, it is important that you try to avoid these biases on your way to becoming a pro at wine sensory.